Parashat Matot–Masei and Rosh Chodesh Av

Numbers 30:2–36:13 (Matot–Masei), Numbers 28:9–15 (Rosh Chodesh), Isaiah 66:1–24 (Rosh Chodesh)

The double portion Matot–Masei concludes the Book of Numbers. It addresses the laws of vows and recounts the war against Midian. It also describes the settlement of the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and half of Manasseh east of the Jordan. Then follow the listing of the 42 desert journeys, the rules for dividing the Land, the establishment of the cities of refuge, and the question of the inheritance of the daughters of Zelophehad.

In the haftarah, the prophet Isaiah portrays a messianic Jerusalem—a source of peace and a center of universal worship.

Numbers 33:33

וַיִּסְעוּ, מֵחֹר הַגִּדְגָּד; וַיַּחֲנוּ, בְּיָטְבָתָה

They journeyed from Hor‑Hagidgad and camped at Yotvata.

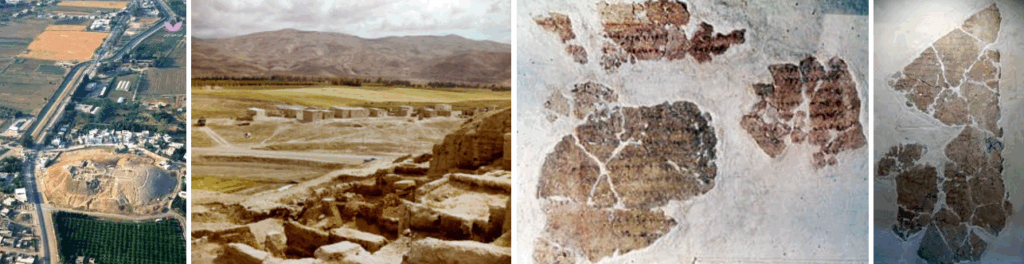

This verse names Yotvata[2] among the 42 stations of Israel’s desert wanderings. When history takes root, the desert becomes fertile.

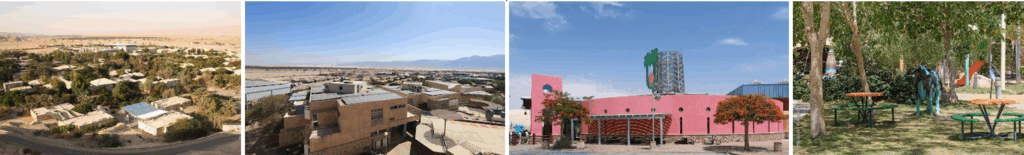

Kibbutz Yotvata was founded in 1957 by the Naḥal movement[3], near Ein Radian—a major natural spring in the Arava Valley, 42 km north of Eilat—adjacent to the ruins of a Roman fort.

From its inception, Yotvata established the regional school Ma’aleh Shaharut[4], which blends academic studies, environmental awareness, and civic engagement. The kibbutz also hosts a boarding program of Na’alé[5].

In the 1960s, an agricultural center combined geological and agronomic research, irrigation innovations, and greenhouse cultivation. Solar panels now supply much of the kibbutz’s electricity, and wastewater is recycled for irrigation.

The Yotvata dairy[6], founded in 1962, processes local milk into over forty products distributed throughout Israel.

Adjacent to the kibbutz, the Hai‑Bar reserve works to reintroduce biblical species to the Negev—onager, oryx, gazelle, and hyena.

[1] Inyan ha‑yom – The subject of the day primes. When a special haftarah is prescribed (e.g., Rosh Chodesh, Hanukkah), it takes precedence over the regular weekly haftarah (Orach Ḥayim 425:1; Mishnah Berurah 425:7).

[2] Deuteronomy 10:7 calls Yotvata “a land of flowing streams.” Some commentaries link its name to the Hebrew root T‑V‑B (tov, “good”).

[3] Naḥal (Noʿar Ḥalutzi Loḥem) – “Fighting Pioneer Youth,” an IDF framework founded in 1948 to combine military service with founding agricultural settlements.

[4] Ma’aleh Shaharut School serves about 600 students from the eleven communities of the Hevel Eilot Regional Council, including Yotvata. Under Israel’s Ministry of Education, it offers pluralistic academic, environmental, and civic education.

[5] Na’alé (Noʿar Oleh Lifnei Horim) – a government program launched in 1992 bringing Jewish teens worldwide to finish high school in Israel before their families make aliyah.

[6] The Yotvata dairy, operated since 2000 in partnership with Strauss Group, is renowned for its chocolate milk and dairy drinks.