Yitro (יתרו – Jethro)

Exodus 18:1–20:23 – (Sephardi) Isaiah 6:1–13 – (Ashkenazi) Isaiah 6:1–7:13

Yitro joins Moses and advises him to establish a judicial structure to lighten his burden. The people of Israel arrive at the foot of Mount Sinai and, after a period of purification, receive the Ten Utterances (Aseret ha‑Dibrot). In the haftarah, Isaiah describes his vision of God enthroned and surrounded by seraphim; once purified, he is sent on a prophetic mission. The Ashkenazi reading continues with the announcement of a sign intended to reassure King Ahaz.

Exodus 18:12

וַיִּקַּח יִתְרוֹ חֹתֵן מֹשֶׁה, עֹלָה וּזְבָחִים לֵאלֹקִים; וַיָּבֹא אַהֲרֹן וְכֹל זִקְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל, לֶאֱכָל־לֶחֶם עִם־חֹתֵן מֹשֶׁה לִפְנֵי הָאֱלֹקִים.

Jethro, Moses’ father‑in‑law, offered a burnt offering and other sacrifices to God; Aaron and all the elders of Israel came to eat bread with Moses’ father‑in‑law in the presence of God.

Rashi notes in his commentary that Yitro entered “under the wings of the Shekhinah” (נכנס תחת כנפי השכינה), an expression indicating his conversion[1].

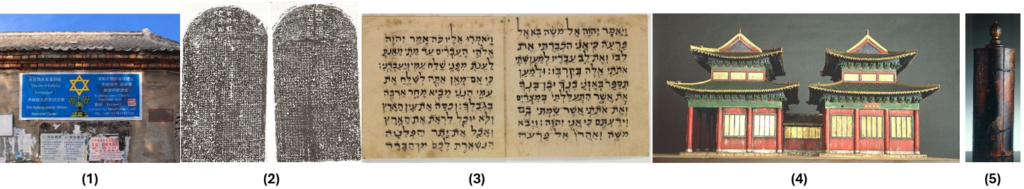

Starting in the 8th century, the Khazar elite adopted Judaism. The most valuable accounts of this conversion appear in the Hebrew correspondence between Ḥasdai ibn Shaprut[2] and King Joseph of the Khazars[3]. In his letter, Joseph recounts his lineage, the conversion of his ancestor Bulan, the establishment of a state governed by Jewish rulers, the creation of religious institutions, the adoption of Torah law by the ruling dynasty, the administrative use of Hebrew, and the presence of an influential Jewish community at court.

Excavations at Sarkel — a name probably derived from the Turkic šar (white) and kel/kil (fortress) — were conducted in the 1930s under Mikhail Artamonov[4], before the site was submerged beneath the Tsimlyansk Reservoir. Archaeologists uncovered walls built of white limestone blocks, granaries and storehouses, and residential quarters. Some of the artifacts unearthed there — including a carved stone bearing a menorah, seals, and tamgas (emblems) — are preserved in the museum of Novochekassk, in the Rostov region.

[1] Regarding conversion, the Talmud mentions ritual immersion (Yevamot 46a–47b) and a korban ger, a sacrifice offered at the Temple (Kritot 9a). For men, conversion also includes circumcision (brit milah or hatafat dam brit – Yevamot 46a). Maimonides specifies that the absence of the Temple does not prevent conversion (Issurei Bi’ah 13:5).

[2] Ḥasdai ben Yitzḥak ben Ezra ibn Shaprut (חסדאי בן יצחק בן עזרא אבן שפרוט), a 10th‑century Jewish diplomat, physician, and statesman at the Umayyad court of Cordoba, and protector of the Jewish communities of al‑Andalus.

[3] Joseph, king of the Khazars in the 10th century. Besides his letter to Ḥasdai, his reign is supported by the Schechter Letter (Cairo Geniza), by several Arab geographers of the 9th–10th centuries (al‑Masʿūdī, Ibn al‑Faqīh, al‑Istakhrī, Ibn Ḥawqal), and by Byzantine chroniclers. He presents himself as a descendant of Bulan, followed by Obadiah, Ḥizqiyah, Manasseh, Ḥanukkah, Isaac, Zebulun, Moses, Nissi, Menaḥem, Benjamin, and Aharon. A document dated 985 also mentions David, prince of the Khazars, who may have succeeded him in a later Khazar polity on the Taman Peninsula.

[4] Mikhail Illarionovich Artamonov (1898‑1972), Russian and Soviet historian, archaeologist, and professor, considered the founding figure of Khazar studies; he authored History of the Khazars (1962), the standard reference on the subject.