Be’houqotaï (בחוקותי – according to My rules),

Leviticus 26:3–27:34 and Jeremiah 16:19–17:14.

Following the blessings and curses, the end of the Sidra is dedicated to the tithe offerings.

Leviticus 27:30

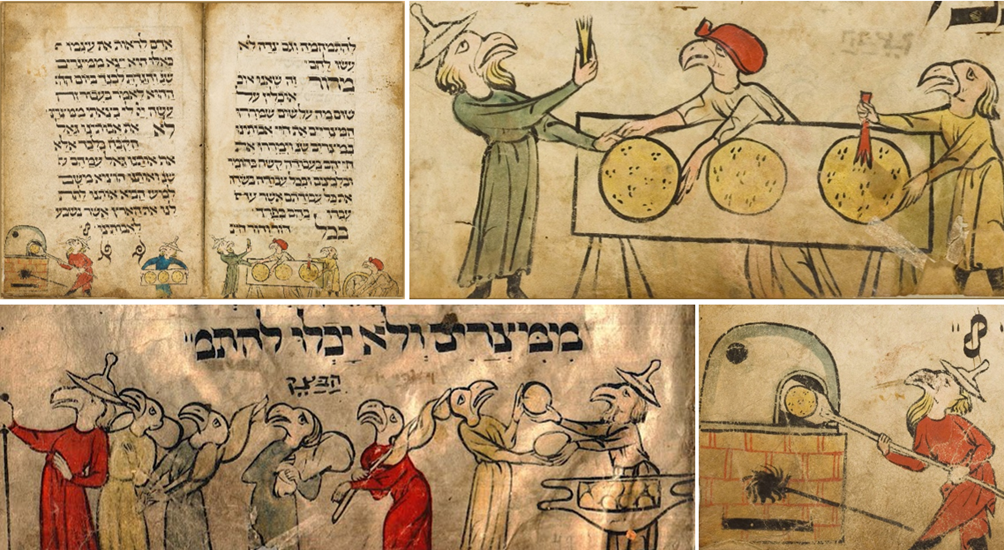

וְכָל-מַעְשַׂר הָאָרֶץ מִזֶּרַע הָאָרֶץ, מִפְּרִי הָעֵץ–לַיי, הוּא: קֹדֶשׁ, לַיי

All the tithe of the land, whether of the seed of the land or of the fruit of the trees, is the Lord’s: it is holy to the Lord.

The Synagogue on Rue de la Dîme (tithe street) in Benfeld was erected in 1846. In 1876, it underwent expansion on the sides by architect Gustave Adolphe Beyer. In 1895, the Wetzel organ (1) was installed. In 1922, orientalist frescoes inspired by those in the Florence synagogue were painted by Benfeld artist Achille Metzger. Recognized for its historical value, the synagogue has been listed as a historical monument since 1984. Currently, it is undergoing restoration as part of the Mission Patrimoine (2).

During World War II, Eugène Guthapfel courageously faced the German authorities and saved the synagogue from destruction (3). Today, a commemorative plaque thanking him is placed outside the synagogue.

(1) It is signed “Ch. Wetzel & Fils, Strasbourg,” meaning by Charles Wetzel and his son Edgard. It is the only remaining synagogue organ in Alsace.

(2) The Mission Patrimoine, entrusted to Stéphane Bern, is a project implemented by the Fondation du Patrimoine and supported by the Ministry of Culture and the Française des Jeux to safeguard French heritage.

(3) As the town hall secretary at the time, he showed remarkable presence of mind. While some nuns hid the religious objects that revealed the building’s religious identity, Eugène Guthapfel claimed to need the synagogue for supposed meetings. Thanks to this ruse, the entire building was preserved.